- Home

- Margaret Erhart

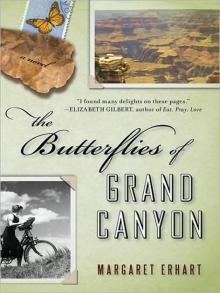

The Butterflies of Grand Canyon

The Butterflies of Grand Canyon Read online

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Acknowledgements

A Silver Ringing

A Tower of Good Intentions

Over the Edge

No Traces

A Man’s Plate

The Myth at Home

The Perfect Confidante

No Place for Corpses

A Patriot

An Impersonator

Her Rubicon

A Gentleman’s Correspondence

A Packet of Liverwurst

The Hour of No Shadow

A Road Trip

More Than One Secret

Guessing Game

The Cause of Suffering

An Inconsiderate Omission

A Dinner Party

Humming

The Same Shirt

Clark Kent Calling

The Second Law of Thermodynamics

A Bullet to the Head

Anax Junius

In the Belly of the Edith

The Monarch Census

Vespids Under Her Veil

A Botanist’s Breakfast

A Slow Walk Home

The Week’s Mail

Billy Bones

The Miracle of Travel

Wits and Teeth

Confession

Carnal Business

A Serviceable Quilt

Off Broadway

Don Juan’s Hat

Limax Maximus

Afterword

A NOTE FROM THE AUTHOR

A PLUME BOOK THE BUTTERFLIES OF GRAND CANYON

MARGARET ERHART is the author of five novels. Her fourth, Crossing Bully Creek, won the Milkweed National Fiction Prize. Her essays have appeared in The New York Times, The Christian Science Monitor, and in several anthologies, including The Best American Spiritual Writing 2005. Her commentaries have aired on National Public Radio. She lives in Flagstaff, Arizona, and teaches creative writing to elementary school students. She is a hiking guide in Grand Canyon.

Praise for Crossing Bully Creek

“Erhart’s descriptions of her characters are reminiscent of Jane Austen’s, in their devastating precision.”—Los Angeles Times

“Crossing Bully Creek is likely to be mentioned in the same breath with Faulkner because they share some commendable commonalities.”—The Historical Novels

“Erhart’s well-crafted, compelling portrait of the Deep South from the Depression to the Vietnam era swings back and forth in time.”—Booklist

Praise for Old Love

“The author of the marvelous Augusta Cotton gives us another quiet novel that reverberates to the depths of the soul.”

—Booklist

Praise for Augusta Cotton

“Engaging . . . Erhart movingly portrays her protagonists contending with more of life than they can grasp.”

—Publishers Weekly

Praise for Unusual Company

“The novel unfolds like a movie.”—The New York Times

Queen

Old World Swallowtail

PLUME

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. • Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) • Penguin Books Ltd., 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England • Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd.) • Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty. Ltd.) • Penguin Books India Pvt. Ltd., 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi - 110 017, India • Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd.) • Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty.) Ltd., 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd., Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published by Plume, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

First Printing, January 2010

Copyright © Margaret Erhart, 2009

Illustrations by Ann Hadley

All rights reserved

REGISTERED TRADEMARK—MARCA REGISTRADA

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Erhart, Margaret.

The butterflies of Grand Canyon / Margaret Erhart.

p. cm.

eISBN : 978-1-101-15971-2

(Ariz.)—Fiction. 3. Domestic fiction. 4. Nineteen fifties—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3555.R426B88 2010

813’.54—dc22 2009034102

Kirch

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

PUBLISHER’S NOTE

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

BOOKS ARE AVAILABLE AT QUANTITY DISCOUNTS WHEN USED TO PROMOTE PRODUCTS OR SERVICES. FOR INFORMATION PLEASE WRITE TO PREMIUM MARKETING DIVISION, PENGUIN GROUP (USA) INC., 375 HUDSON STREET, NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10014

http://us.penguingroup.com

For my father, who loved the river

that runs through Grand Canyon

By now, it is well known that the picture of the scientist as the

eccentric personality without human feeling, pursuing truth

by the numbers, wearing sterile gloves at all times, is false.

But the particular way that a person trained in logical thinking

must negotiate his or her way through the illogical world of

human passions—that is a subject worthy of art.

Alan Lightman, Nature magazine, March 17, 2005

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

As a fiction writer, I am more apt to foray into the realm of motive than I am into a world of scientific data. But this book called for facts, and in this area my guides were many, past and present. Dr. Larry Stevens shared his prodigious knowledge and curiosity about every bit of flora and fauna in the Grand Canyon region, and especially the butterflies. Glenn Rink, a modern-day Elzada Clover, helped out with cacti. Christa Sadler made the rocks come alive, and Northern Arizona University’s Cline Library provided me with an excellent collection of photographs and correspondence that breathed life into the historical characters who populate this novel. I am especially indebted to Louise Hinchliffe, Preston Schellbach, and Steve Verkamp, who shared their memories of the South Rim and the people who lived there in the 1950s. Kim Besom and Colleen Hyde made the Grand Canyon Museum Collection available to me. Jim Babbitt generously offered historical information about Flagstaff. For critical readings of the manuscript in all its many incarnations I would like to thank Ann Baker, Stephany Brown, Stephen Erhart, Victoria Erhart, Rose Houk, Warren Perkins, and Ann Walka. Tony Hoagland, poet and friend, provided H. C. Bryant with the title What Narcissism Means to Me. Ann Hadley drew the butterflies. Countless others, with whom I’ve hiked or run the river, have contributed to this book by their contagious passion for a place—this place—Grand Canyon. To them I say thank you and read on.

Prologue

GRAPEVINE RAPID, 1938

The trail to the river is steep, the footing unreliable. An animal track is what it is. Bighorn sheep, mule deer. Water is life and takes life, as he well knows.

His traveling companion has the pale, fleshy look of an in doorsman. Last night they camped at Cottonwood Creek, and the city man complained of the food while above them the stars spread thin and bright across a blue-black bucket of sky. The man likes it here where the canyon opens and the sky is broad, but the city man took no interest in what hung above them. Instead, he opined on the scarcity of flavor in his tinned stew.

The man showered this morning at the pourover down canyon and air-dried in the shade of a cottonwood—it was shade hot already. The city man scarcely wet his head. He’d brought a comb and stood over a pool, grooming his reflection. It was then the conversation turned muddy. He asked about the gun, and the man in the shade said it was nothing; he carried it out of habit and duty. The city man let on he didn’t believe that, but he wasn’t a coward either. Maybe there were dangers—lion or bear? The man in the shade nodded without saying yes.

Now they’ve hiked out a few miles to the west and come to the cairn that marks the vertical trail. The ground is soft and clouds of dust rise behind their boots as they descend. The city man pants with the effort of holding back. He can see the river below him, the liquid tongue of a rapid. He can feel it wanting him, drawing him downward. His thighs burn and his legs shake. He’s afraid of falling and certain of it. He calls ahead to the other and says, “I’m going back.” He turns, but in turning dislodges a rock that starts the earth around him sinking and sliding, and he slides with it, grabbing with his good arm at roots and rocks and a flat green cactus. The sky above him is dressed for a storm and he sees it. All the while he hears the sound below, the rapid’s deep exhalation, like the openmouthed breathing of a heavy sleeper.

Later, on the way up, the man removes his pistol and thinks to throw it in the river from above. But he buries it in his pocket again and climbs with the agility of an unburdened traveler. His lungs fill and empty, and he can feel their rhythm and that of his heart. Briefly, he thinks of Gracia, though he does not allow himself to feel victorious. It has not gone as he wished. There was no suitable ending. The rain is behind him. He can feel it, a light spray borne by the wind. The air is cool, almost cold, the noise of thunder sharp and increasing. An urgency compels him as he gains the flat ground and hurries eastward, stopping at the creek only to eat and fill his canteen with water.

A Silver Ringing

The surprise to her is not how large the mountain looms but that it is, on the twenty-ninth of June, entirely covered with snow. The light is failing as Mr. and Mrs. Morris Merkle arrive at last at the little station in Flagstaff, Arizona. They see what appears to be a grubby town, but behind it stands a most awe-inspiring sight, an eloquent chapter in prehuman history: the San Francisco Peaks. It is not a chapter they have ever read before, or even conceived of, living in St. Louis.

Relieved to escape the train, they stumble across the platform, searching for their luggage and the Hedquists. Morris Merkle is experiencing some trouble breathing. Jane, his young wife, has a headache but hardly notices. It is cool, almost cold. Only a handful of people have gotten off the train, some of them just to stretch their legs. The station building is lit up inside. In the distance, high up against the darkening sky, a few gaudy neon signs advertise hotels—the DuBeau, the Downtowner, the Monte Vista. Fleabags, surely, thinks Mrs. Merkle.

Suddenly Morris calls out, “Dotty! Dotty, darling! Over here!” and walks quickly in the direction of a long-legged woman wearing a pair of dark slacks and a short canvas coat. Her face resembles his; her long graying hair is rolled in a bun in a way that nevertheless fails to make her look school marmish. Jane Merkle has no recollection of this particular Dotty Hedquist. It has been two years since they last saw each other, and her memory of her sister-in-law is less complimentary, less womanly. In fact, in a shallow recess of her mind she wonders if there has been some change, some rearrangement in relationship perhaps, some affection or appreciation coming to Dotty from a quarter not connected to her marriage. These things have been known to make a dour woman glow.

“Jane, dear,” says Dotty, and with great effort gives her sister-in-law a stiff hug, followed by a peck on the cheek. Jane feels almost as if she has been bitten. Dotty holds her at arm’s length. “What a lovely dress you have on. It suits your youth. Quite the fashion, I imagine, though out here nobody pays much attention to any of that. You look so fresh!”

Oliver Hedquist heartily shakes Jane’s hand, as he always does, and suggests they round up the luggage. The train whistle sounds, and the trainmen beam their lanterns under the wheels while the conductors hop aboard and in slow motion pull up the metal steps. The cars rumble by, gaining speed, shaking the ground, until the last one passes and there across the tracks lies the other half of town.

There are three bags on the platform. One of them is a large leather suitcase belonging to Morris Merkle, who, though he is not prone to thoughts like these, finds it almost an act of magic that he can pack shirts and shoes and trousers and socks and underwear and a good jacket or two into a defined rectangular space in St. Louis, Missouri, and without much attention to the process on his part, the whole lot arrives in Flagstaff, Arizona, and awaits him on the platform. He begins to walk away with his retrieved belongings. His brother-in-law points him toward the car. But Jane is not so caught up in the magic as her husband, for she has discovered that, of the three items on the platform, one belongs to her husband and the two others to a couple of mismatched ladies who rode the train from Chicago. One wears trousers, the other an orange dress. They are obviously old friends, traveling lightly. Yet she who packed a footlocker full of her favorite dresses and skirts and fancy blouses, and her good hairbrush with real sow bristles and a monogrammed silver back, is left in this new land with what she’s wearing and the contents of her purse. This is the sum of it, and it will have to do until she finds a shop, which will surely not be this evening, or perhaps anytime soon. And as for borrowing clothes from Dotty, she quickly decides she would rather throw herself beneath a train. Jane Merkle has never believed in slacks beyond the confines of the home, except in winter when she has to shovel snow, and she strongly suspects, from earlier comments, that slacks are all poor Dotty’s got. And yes, her sister-in-law cuts an impressive figure in them these days, but Jane does not, she’s certain she does not, and she won’t look a fool for the sake of conformity. When in Rome remember you’re from St. Louis—that’s her motto.

After much apologizing on the part of Oliver Hedquist for the loss of Jane Merkle’s wardrobe, though in what way he might be responsible even he can’t figure out, they pile into the Chevrolet and head off to find, in his words, “something to chew on.” Jane Merkle hopes it won’t be anything too old or tough or spicy. There are a few Chinese restaurants along the main road, which is the famous Route 66, Oliver informs them. Jane wills the car not to stop at these places, which are dimly lit and steamy, each with an old Oriental woman sitting by the window, gazing out. The car goes on, and finally they come to a Howard Johnson’s. Oliver Hedquist pulls into the empty parking lot and Dotty says, “It’s too cold for ice cream, Oliver.” To which he responds, “I’m afraid I’ve got my heart set on fried clams.”

They hurry inside and Jane, who hasn’t had one in years, orders a chocolate milk shake. Dotty has a chicken sandwich and iced tea. The men order clams, followed by pie and coffee. Finally Oliver says, “Well, you two must be tuckered out, and we’ve got a drive ahead of us. Shall we?”

Jane dozes in the backseat and wakes to the swerving motion of the car and the dreamlike sight of two deer caught in the headlights, leaping across the road. Morris sleeps upright with his head against the window. She takes his hand, and he snuffles like a piglet and gently begins to snore. Later, in the Hedquists’ home, in the bed she must share with her husband, Jane lies a

wake and considers the strangeness of having arrived at last at the Grand Canyon and found, to her great surprise, there was nothing to see, nothing but darkness. Despite the hour, Oliver had not driven them straight home but to the lodge on the rim, where he and Jane walked the few steps out to the edge of the canyon, which might have been the edge of the world. And behold! A great nothing! She must have expressed her disappointment, to which he replied, “Well, of course. There’s no moon. You can’t expect to see much. But there’s no wind tonight, so you can hear it.”

“Hear what?” asked Jane.

“Listen.”

She listened. She struggled and strained to listen, and heard nothing. “I’m afraid I don’t hear a thing.”

“But you do,” he encouraged her. “You’ve never thought of it as sound. You’ve thought of it as the absence of sound. It’s that ringing.”

She prayed to hear something ring. She wanted to please the old man. And just as she had given up and was about to lie—a little white lie—by saying, “Yes, of course. That ringing,” she did hear it. How extraordinary. As loud as a swarm of mosquitoes, but set in a higher octave, and continuous. One continuous, clear, high-pitched silver ringing. The sound of the Grand Canyon. She laughed, and he did too. He placed his hand on her elbow, turning her in the dark, and without another word they walked back to the car.

The next morning her husband is not in the bed. She walks through the house and finds him in the kitchen, trying his hand at coffee.

“Morris?” She tries not to sound incredulous.

“Ah, dearest, good morning. I’m just . . . creating something here.”

The Butterflies of Grand Canyon

The Butterflies of Grand Canyon